Untangling the Web of Babies’ Sleep, Moms’ Sleep, and Depression

When Kate Love thinks about the early days of her son’s life, she remembers working jobs as a bartender or waitress until 2 a.m. She remembers coming home and being alone with her son as a single mom facing the many unknowns of first-time motherhood. She remembers being lonely, facing the reality of her postpartum depression — and the effects of many sleepless nights.

“I felt like I got swallowed up by the depression,” says Love, who lives in Boulder, Colorado. “Those first few months, I was maybe getting an hour of sleep a night.”

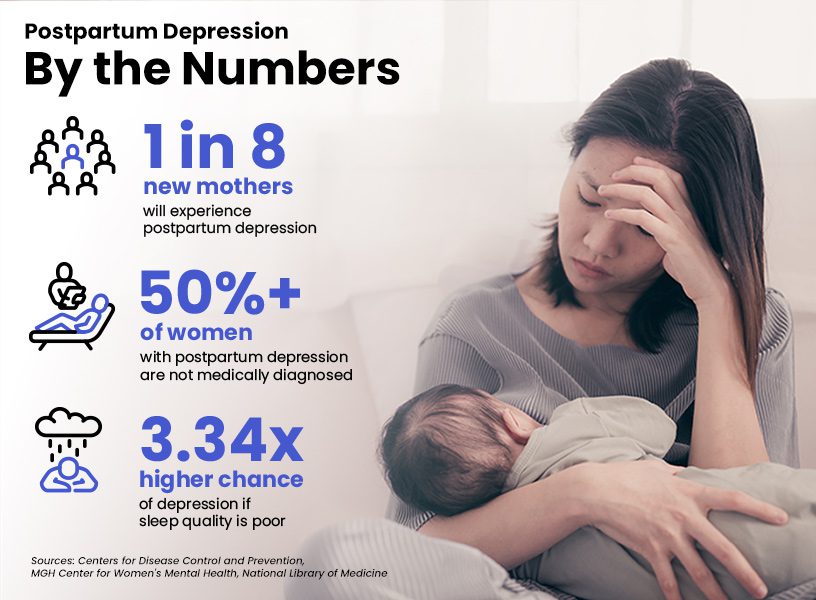

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention , roughly 1 in 8 new mothers will experience postpartum depression, which occurs after birth and can last indefinitely. It can impact moms’ ability to sleep. It can also have long-term effects on babies’ sleep, according to a new study .

As moms’ sleep deprivation continues to be a problem that families of all types try to solve, ensuring everyone gets the sleep their bodies need comes into sharper focus.

‘No One Was Sleeping’

Love says she experienced feelings of depression before her son’s birth more than 12 years ago. At that time, she’d sleep long hours.

“Once my son was in the picture, my coping strategies began to affect him,” Love says. “He wanted to oversleep like I did, and I still see it in him today. He has a tendency to want to oversleep to this day, and that lack of feeling recharged in the morning can be hard for both of us.”

This effect on mothers as well as their children was outlined in the Shanghai-based study of 243 Chinese mothers. In addition to finding an association between short daytime sleep in infants and postpartum depression in mothers, researchers looked at the deeper effects from birth to when the mothers’ children were 3 years old. The results showed that children are more likely to have short daytime sleep and persistent night-waking if their mothers experienced postpartum depression within two months after childbirth.

Where does this all start? Look first at the sudden hormone drop that happens after birth. This drop is linked to postpartum depression, as well as sleep deprivation that may be the result of an infant’s sporadic and challenging sleep schedule.

This lack of sleep for new parents then poses a health risk, says Dr. Nilong Vyas, a pediatrician and sleep coach.

Children are more likely to have short daytime sleep and persistent night-waking if their mothers experienced postpartum depression within two months after childbirth.

“Sleep deprivation for 18 hours, which is common in a new nursing mother, is equivalent to a blood alcohol level of 0.05%,” she says. That’s about the same effect as at least one alcoholic drink for a female who weighs 90 pounds or more. “So many parents are walking around ‘drunk’ while expected to parent, drive, and work.”

Unhealthy sleep itself also can worsen symptoms of depression. A 2018 study found that postpartum depression symptoms worsened if a mother can’t regain a normal sleep schedule, which is tied to a baby’s sleep schedule. Women who reported issues around falling asleep at night and had difficulty staying awake during the day experienced longer bouts of depression.

It also can keep other members of the household up at night. Jade Kearney, a New York-based businesswoman and mother, says that her postpartum depression experience led to severe sleep deprivation with the birth of her first child. With the birth of her second, it expanded.

“My newborn had colic and didn’t sleep those first three months at all,” Kearney said. “My 3-year-old at the time, who is now 4, was trying to understand why the baby’s crying through the night.

“She wasn’t sleeping. I wasn’t sleeping. Dad wasn’t sleeping. No one was sleeping.”

Coping With ‘Inevitable’ Sleep Issues That Come With Motherhood

The prevailing thought may be that all of this sleeplessness is normal, to an extent.

Kate Kripke, senior supervising psychotherapist and founding director of the Postpartum Wellness Center in Boulder, says that many mothers she works with assume they will not be sleeping. There’s some merit to it: One study suggests that mothers with postpartum depression sleep 80 minutes less per night than those without it.

This postpartum insomnia comes at a cost.

“Parents can have a ‘I must do this on my own' attitude, but they must ask for help and understand that parenting is not a sprint; it is a marathon.” — Dr. Nilong Vyas, pediatrician and sleep consultant

“We throw the term ‘sleep deprivation’ around like it’s no big deal, but you don’t find sleep deprivation without depression and anxiety,” Kripke says. “Our primary goal is to make sure mothers are getting enough sleep so that their brains can function and be resilient to the type of stressors that are inevitable in early parenting and early mothering.”

In turn, these issues may spread. Kripke says that maternal mental-health challenges are the leading causes of the childhood mental-health issues she sees at her clinic.

“When we’re supporting the mom, we’re not just supporting the mom,” she says. “We’re supporting the mental health of the babies and kids.”

The idea of stopping to recharge or engage in postpartum care goes on the backburner once a child is born, Dr. Vyas says.

“Parents can have an ‘I must do this on my own’ attitude, but they must ask for help and understand that parenting is not a sprint; it is a marathon,” she says.

Anxiety Has Entered the Chat

Kearney says her sleepless nights involved being woken up by anxiety-driven panic attacks. After a certain point of exhaustion, Kearney remembers the dysfunction extending beyond her home.

“My interactions at work were terrible,” Kearney says. “I was failing at everything I was doing.”

It culminated in an errand that turned into what she calls “a hurricane of chaos.”

“I remember getting out of my car, and for a few seconds, I had no idea where I was,” Kearney says, reflecting on the terror she felt in that moment. “I know that moment happened because I wasn’t sleeping. My postpartum depression had caused severe anxiety, and I couldn’t sleep.”

Through her clinic work, Kripke says she learned that sleep is the first thing to go for anxious mothers. Nearly 50% of people with anxiety also have a depression disorder.

“We don’t sleep unless we feel safe,” Kripke says. “If our nervous system is agitated, our bodies are not prepared to sleep and certainly not prepared to sleep well.”

Other factors can contribute to this feeling. Kearney recognized that there was a lack of support for Black mothers in the healthcare system, specifically around mental health because of cultural stigmas and inequity. Black mothers are less likely to seek treatment for postpartum depression than non-Black mothers.

With her business partner, Marguerite Pierce, Kearney developed the app SheMatters. It’s an online platform focused on connecting Black mothers with others going through postpartum depression and anxiety. It also helps these moms find relevant resources and therapists.

“Some of us have experienced violence and the feeling of not being safe, from the moment of conception,” Kearney says. “So we, during our postpartum period, are exhausted not only in the way that other moms are exhausted, but we’re also exhausted because, in this country, we are treated unfairly.”

“When we're supporting the mom, we're not just supporting the mom. We're supporting the mental health of the babies and kids.” — Kate Kripke, Postpartum Wellness Center

There also may be pressures from work (or not working) and mothers losing part of their identity. The average age of first-time mothers in America has increased from 21 in 1980 to 26 in 2016, according to research from The New York Times.

“When we see women having babies later in life, the mothers have often established themselves as professionals in the world,” Kripke says. “They might find themselves wondering, ‘Whoa, where did I go?’ after giving birth because their lives change so dramatically, which can spur depression and sleep loss.”

Clearing Up Misconceptions and Finding Support

Kripke says that one of the most common misconceptions about a mother going through any sort of mood or mental health challenges is that she is a bad mom or has the impression she is.

“We’re told that good mothers are supposed to love mothering, but not all good mothers love mothering,” Kripke says. “A mom can feel angry or depressed or resent her baby in moments, but that doesn’t make her a bad mom. But it certainly can bring up feelings of shame.”

Because of stigmatized assumptions surrounding postpartum, Kripke says a lot of the breakthroughs with new mothers and their sleep come from education. This comes from an emphasis on sleep hygiene for mothers to help them feel confident in their ability to rest and to pass that along to their children.

“When we can re-educate around what it means to be a good mother, that opens a window to prioritize things like sleep,” Kripke says.

This support works both ways. Dr. Vyas says support systems are key in the early stages of a child’s life, particularly when coupled with a mother coping with postpartum depression.

“In the initial weeks of the newborn’s life, regardless if a mother is suffering with postpartum depression or not, the focus is on ensuring adequate intake for the infant and healing for the mother,” she says. “Many of the habits and schedules surrounding sleep can be implemented once there is stability on that front.”

Using cognitive behavioral therapy strategies, Kripke says she helps mothers combat depression-related insomnia symptoms that can arise from the constant stress of being a “bad mom.”

“When we can re-educate around what it means to be a good mother, that opens a window to prioritize things like sleep.”

— Kate Kripke, Postpartum Wellness Center

“We do a lot of mindfulness work with our clients around insomnia, so they can get out of their own way and settle down enough to fall asleep,” Kripke says.

If moms can teach themselves to sleep, she says, they can teach their kids to sleep, too.

“They mirror us,” Kripke says. “The child will have more space to be healthy in their lives if we’re healthy in ours.”

Love says her sleep has gotten better but that she has work to do. She is through the worst of her postpartum depression, but she can recall the isolation and hopelessness she experienced early in motherhood.

As a doula, she has used those memories to lay the groundwork for new mothers to get a good night’s sleep. She shares solutions for mothers, emotionally and physically.

“I think it’s important for moms who are experiencing depression to have kindness for themselves,” Love says. “Open yourself up as much as you can to curiosity when it comes to your healing, and hopefully, that will help deepen your connection with your baby.”

References

8 Sources

-

Bauman BL, Ko JY, Cox S, et al. Vital Signs: Postpartum Depressive Symptoms and Provider Discussions About Perinatal Depression — United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:575–581.

https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6919a2.htm?s_cid=mm6919a2_w -

Yiding Gui, Yujiao Deng, Xiaoning Sun, Wen Li, Tingyu Rong, Xuelai Wang, Yanrui Jiang, Qi Zhu, Jianghong Liu, Guanghai Wang, Fan Jiang, Early childhood sleep trajectories and association with maternal depression: a prospective cohort study, Sleep, 2022;, zsac037,

https://academic.oup.com/sleep/article/doi/10.1093/sleep/zsac037/6528988 -

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. FAQ: Postpartum Depression., Retrieved May 5, 2022.

https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/postpartum-depression -

Lewis, B. A., Gjerdingen, D., Schuver, K., Avery, M., & Marcus, B. H. (2018). The effect of sleep pattern changes on postpartum depressive symptoms. BMC women’s health, 18(1), 12.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29316912/ -

Lee, K. A., McEnany, G., & Zaffke, M. E. (2000). REM sleep and mood state in childbearing women: sleepy or weepy?. Sleep, 23(7), 877–885.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11083596/ -

Anxiety and Depression Society of America. Understanding Anxiety and Depression, Facts and Statistics., Retrieved May 4, 2022.

https://adaa.org/understanding-anxiety/facts-statistics -

Kozhimannil, K. B., Trinacty, C. M., Busch, A. B., Huskamp, H. A., & Adams, A. S. (2011). Racial and ethnic disparities in postpartum depression care among low-income women. Psychiatric services (Washington, D.C.), 62(6), 619–625.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3733216/ -

Quoctrung Bui and Claire Cain Miller. The Age That Women Have Babies: How a Gap Divides America. The New York Times. (August 3, 2018)., Retrieved May 4, 2022.

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/08/04/upshot/up-birth-age-gap.html?mtrref=www.google.com&assetType=PAYWALL&mtrref=www.nytimes.com&assetType=PAYWALL